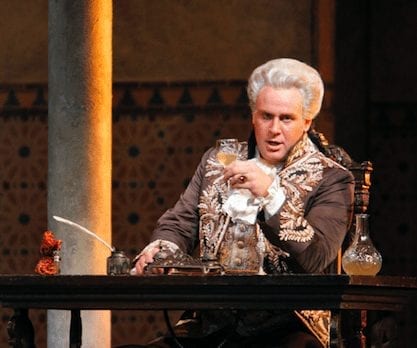

Here I am in the sunny Spanish countryside, about to sing my 6th production of Le Nozze di Figaro as The Count. I figured it was about time I gave my thoughts on the man that is loathed by the audience but much loved by his own self.

I love having the chance to delve into the mind of this aristocrat. What have I learned over the years portraying such a selfish and scheming nobleman?

Let’s find out!

An 18th Century Narcissist

The Count is a mediocre man from a prestigious family.

He’s not the Charlemagne or King Louis of his time, but he’s a nobleman who demands respect from others. He lives in a world he and his aristocratic equals have created, and there he is a confident man. In the real world, however, he lacks that same confidence. He’s a wannabe playboy who chases after the servant girls. He wants not only to be in charge of everyone, yet also in control. But that control is slipping…

The reality is that these characters are on the cusp of the French Revolution, and the servants are fed up. Nevertheless, until the chants of “Off with their heads” begin, he is still at the mast of the house. That’s what makes the ending such a surprise for him: when he falls for an elaborate scheme by his servants and wife.

Before his philandering days, besides being a bit spoiled, the Count was actually a good guy. In the prequel to Nozze, Il Barbiere di Sivilgia, he fell hard and fast for the beautiful, yet trapped, Rosina. For him, the chase was more exciting than the prize. This youthful love fizzled out quickly, and the passion and intrigue dwindled for him. Rosina was also mislead, because she wanted the Count all to herself. As such, she ends up in a different prison than the one from before: she has no freedom or opinions. Out of all the characters in this opera, I feel the most sorry for the Countess.

I wouldn’t say it was true love, more like true lust. It’s easy to see how their marriage failed, when the Count hauled her off from Seville before they had even a single conversation alone together. In Barbiere, their only interactions happened in hush tones and in costume.

Droit du seigneur

The most significant component of the opera is the archaic custom known as droit du seigneur or “right of the lord”: a lord had the feudal right to sleep with a subordinate woman on her wedding night before her husband did.

It’s evident that the Count used this right quite often, because he says in the opera that he went ahead with abolishing it due to the mounting pressure that was on him. Figaro reminds him of how wonderful the new law is, even though he can tell that the Count hasn’t fully accepted his new decree. Even though he abolished it, he still wants to take advantage of it through back channels with Figaro’s fiancée, Susanna.

The audience sees Figaro, his most loyal servant, and Susanna being taken advantage of by the Count when he wants to re-exercise this right. But that’s not what the Count sees.

The count feels justified in his actions because it is his right to have Susanna on her wedding night.

It’s just like my right today to bear arms and my right to freedom of speech in the United States. It was normal for that time: it was the LAW.

A progressive man himself, Figaro thinks the droit du seigneur is wrong, and the ideas of the impending French Revolution bubble underneath throughout the whole opera. Figaro realizes, “Wait a second, we don’t have to live like this!” And at that moment, the idea of liberty has been planted: he can fight for his rights in the state of a democracy.

Knock, knock. Who’s there? The revolution!

This irks the Count because to him, it is merely his noble birth right. To understand him, you really have to put yourself in the mindset of the time. Much like Don Giovanni and his misconstrued ways.

My Portrayal

In my opinion, people see art through the eyes of the culture in which they live.

Because of this, my biggest mountain to climb with the Count is showing the audience that he really believes in his feudal right, which in turn makes him forgivable in the end, since he’s merely a product of the times.

If he thought, “I’m going to sleep with as many chicks as possible, even though I know it’s wrong,” he’d be much less forgivable. If he were to say, “I deserve this! My father before me and before him were royals!”, you’d see that he’s just a victim of the times.

I like playing such a pivotal character in this opera, because the whole show is centered around the drama he creates. The plot follows Figaro and Susanna as they plan an elaborate farce to teach him a lesson. Art doesn’t move forward without drama, and the person who creates the drama is the antagonist: he’s the true villain of the story.

From my point of view, the lesson the Count learns from this story is not a profound one. He basically learns not to underestimate his wife. And if I’m honest, he learns a second lesson, which is that he should figure out how to be more clever about getting away with things. I think that if there was a fifth act of this opera, he would just try to scheme harder, better, faster, and stronger.

It was once suggested to me that the Count is impotent.*

Think about it.

If he wasn’t, wouldn’t there be several bastard children running around the palace? The feudal right had only recently been abolished, meaning that he had been doing it up until then. Yet, no offspring came from it?

I think that’s telling.

When a man can’t reproduce, then he may overcompensate with his masculinity, which explains the Count hooking up with so many women. Another clue lies in the third installment of this story, The Guilty Mother by Beaumarchais. In the sequel, The Countess gets pregnant by Cherubino, which shows she’s Fertile Myrtle!

I love this interpretation, and I incorporate this into my own characterization. Deep down, my Count is desperate to assert his masculinity over other people, in order to make up for the fact that he’s shooting blanks!

Let’s Talk Technique

In my opinion, the Count isn’t particularly challenging on the vocal side of things. The role doesn’t sit terribly high for a baritone and doesn’t demand too many long legato lines. The parts that excite me the most are the final measures of my aria, the sotto voce lines in the ensembles, and of course, “Contessa, perdono.” That line is just amazing!

What I love most about singing the Count (and this opera) is Mozart’s genius in how he wrote the emotion within the music. Two fiery, dotted, diminished chords convey so much drama to me, and as a performer, I have to show that. The music tells me exactly what emotion to feel, even more than the words do.

I get this sensation every time I sing Mozart, and this emotional painting happens all over the Count’s aria, “Hai gia vinta la causa”.

You can hear his confusion, vulnerability, betrayal, and anger towards his servants, ending with a confident return to his crafty ways.

Flaws And All

Every time I see the show as an audience member, I don’t love the role of the Count because it is flawed. The first two acts are impeccably written, but the third act is a little hard to believe.

For example, if Figaro dances with his broken foot after his feigned injury from Act 2, the Count would most likely send him away somewhere and would not accept his phony explanation of how he’s suddenly able to dance. To me, it’s unbelievable that the Count doesn’t have more of a reaction. The march begins right after, but the Count could have easily stopped the music. The reaction doesn’t live in the reality of the show. It’s an imperfect role, and the audience senses that.

I make sense of it by reasoning that the Count suppresses his emotions because so many people are around. The entire household surrounds him, and he doesn’t have a strong reaction because he doesn’t want to make a scene.

This is just one example of how my mind tries to make sense of some of the moments that don’t feel natural to me as the Count. There is a reason for everything, and I try to look at my personal experiences to discover a true reaction from my characters. For me personally, if I’m in a crowd and I disagree with someone, I do it a lot more nicely or quietly than if I’m alone with them.

A Lesson Learned

Finding the balance between the buffo and dramatic portrayal of the Count is definitely the biggest challenge of this role, and it’s usually dependent on the director. The opera is in the buffo (comedy) style, but the Count can’t be an idiot. He is only one step behind his servants, not twenty. The way to find this balance between comedic and dignified is by going too far in one direction, and then pulling back.

If you’re an opera singer, you’ll know what I mean! The line is barely there, but it is.

One time, I was singing the Count at the Royal Opera House in London. The production was directed by David McVicar, a man who I hold in the highest regard. However, we hadn’t met at that point.

Because he was directing three other shows in London at the same time, I didn’t meet him until the third day of rehearsal. The production of Le Nozze I had just finished, with John Copley, included over-the-top reactions and slapstick gestures. Having just sung in the production, and without David there to direct me, I had brought the Copley Count into the McVicar show.

When David finally arrived to rehearsal, we had staged up until the Act 2 Finale. I was singing away, in front of the cast, the chorus, stage crew, and the directorial team. David held up his hand and stopped me in the middle of the scene. He looked at me with those piercing McVicar eyes and said, “Lucas. What are you doing?” I told him every reason for every choice that I was making, and all of them were correct. But I didn’t realize that all of those reasons had turned the Count into a buffoon!

David told me that it was too much in the extreme and I needed to rethink my entire interpretation: the reactions had to be more subtle. I told him that this would’ve been nice to know since Day 1 (not a good move!). The entire rehearsal had come to a standstill, and everyone was listening to our biting exchange. I was so embarrassed.

He then told me that I play the Count ten steps behind the other characters when in reality I need to play him just a half-step behind them. In that half-step is where the drama lives.

I was crushed. I felt so defeated.

I went home to sulk but instead, I opened my score (and a bottle of wine!). I went through every interaction with a different perspective.

The next day, I showed up and it was terrible. I was Jekyll and Hyde! I was inside and outside of my body. Luckily, David was there to help me along, and was very patient. After another evening alone, buried in my score, I showed up for the next rehearsal and something had clicked. All of a sudden, my moves felt so precise and had so much more meaning to them!

David was right. When he finally saw the new Count, he told me he would have never said anything to me, if he didn’t have faith in my ability to change. Ever since then, this is the way I portray the Count: he takes himself very seriously and is very self-assured. When the Count fails just a half-step behind the rest of the characters, he helps everyone else’s wins be that much more successful!

Moral of the story is: don’t be a caricature of the character, BE THE CHARACTER! And listen to your director!

*My initial post incorrectly stated that the Count is impotent. The correct term for the character’s state is sterile. However, the third installation of Beaumarchais’ play, La Mère coupable, disproves this theory, since the Count has an illegitimate child, Florestine, and this revelation has caused me to rethink the characterization entirely.

Thank you to Judith Johnston and Joanna Barouch for their astute observations. I am so happy to know that such intelligent people read this blog!

For my upcoming performance of Le Nozze de Figaro, my interpretation is that the Count is asserting his masculinity for a different reason: his sexless life with the Countess. They haven’t had a child, so this is plausible. Since he yearns to “do the manly thing” and spread his seed, he feels the need (and thus, the right) to seek sex elsewhere, namely with Susanna.

What do you think? Did you find this article interesting, entertaining, or helpful? Feel free to chime in your thoughts on this subject with a comment below.

This was very insightful and well-written….I learned a lot from it, and would love to see your performance in this role! One question: don’t you mean “sterile” instead of “impotent”?

Hi Judith, please check the blog post for some additions (the very end). Thank you for your astute observations! Please let me know if you end up making a show.

In “LaMere Coupable”,the Count has an illegitimate daughter by an unnamed servant. Not impotent.

Thank you Joanna! I really appreciate you pointing this out. Please check the blog article for a new additional appendix and shoutout! Thanks again.