In just a few weeks, I’m reaching a milestone in my operatic career: my 50th role.

That doesn’t mean years of merely memorizing music; role preparation is a process and an essential part of life as an opera singer. Over the years, I’ve honed that process and I’ve found exactly what works for me in order to take on a new character.

It’s a meticulous and fascinating journey every time I open up a new score. No matter what role I learn, here are the steps I take along the way:

1. Buy The Right Score

First things first! This may seem obvious but it’s a step that can’t afford to be overlooked.

There are many editions of opera scores out there and what works for Puccini is not going to work for Mozart. Different musicologists and editors decide what goes into a score, and you have to choose an accurate source for your music-making.

Bärenreiter is great for Mozart, and Ricordi is good for Puccini, but do your research and ask a coach or conductor before you make that purchase—it can be quite expensive! When I was young, I made the mistake of buying a full opera score (the entire orchestra part) so be smart and order a vocal score (voice and piano reduction).

Some scores have a lot of editorial mistakes, so be sure to crosscheck with other scores, if you can get your hands on them, before making the purchase. You want a score that is reliable.

Make sure you purchase the right version and the one that’s the most stylistically accurate: it’ll show the conductor you mean business at that first rehearsal.

For buying scores, I recommend Classical Vocal Reprints. Amazon has less of the rare works, but they do deliver in two days if you need something fast.

Time-wise, even though it takes me 2-4 months to learn a role, this first step of buying the score happens 5-6 months before that first rehearsal just so I’m extra prepared.

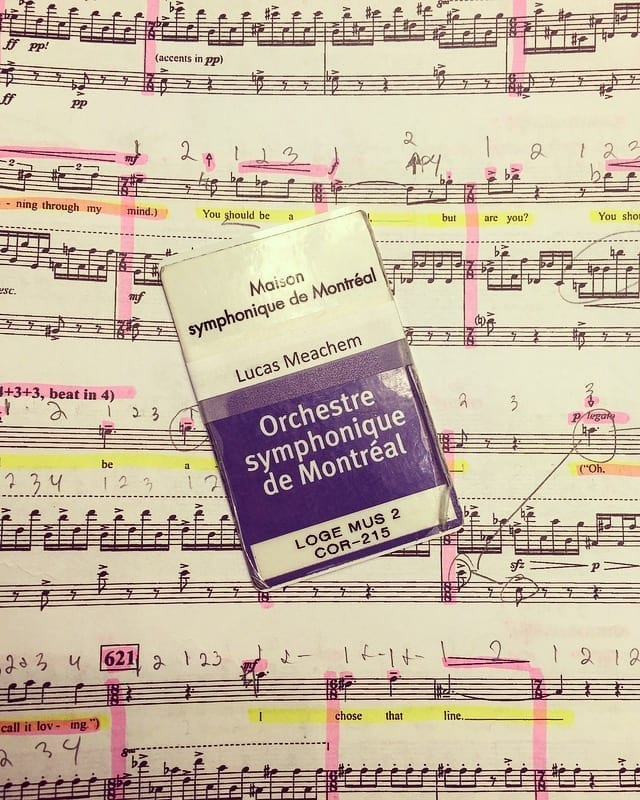

2. Listen to a Recording and Highlight

Find a few solid recordings of the opera—I choose them according to the baritone or the conductor—and grab those highlighters! While listening to a recording, I use a yellow highlighter for all of my text. Next, I use a pink highlighter for any musical indications that may affect my singing (dynamics, meter and tempo changes, articulation, stage directions, etc.).

I listen to a recording right off the bat to get a sense for how the opera flows, the tempi and any traditions that aren’t written in the score. Since I don’t have the role learned yet, the danger of imitation isn’t much of a problem because it’s not in my voice yet. After listening to it once, I don’t refer to it again until the very end of the process because of that same danger.

Listening to a recording can give you some creative ideas for the role as well as an example of what not to do, so stay open-minded as you listen. Remember to make the role unique to yourself while also preserving the tradition of the piece.

Don’t forget tabs: I use these hefty tabs to indicate my entrances. This makes it easier to refer to those places in a rehearsal. I don’t use a different color for arias because it gives the aria more “weight” than it needs. It’s just part of the role. It’s crazy how organization can alter your mindset!

3. Translate

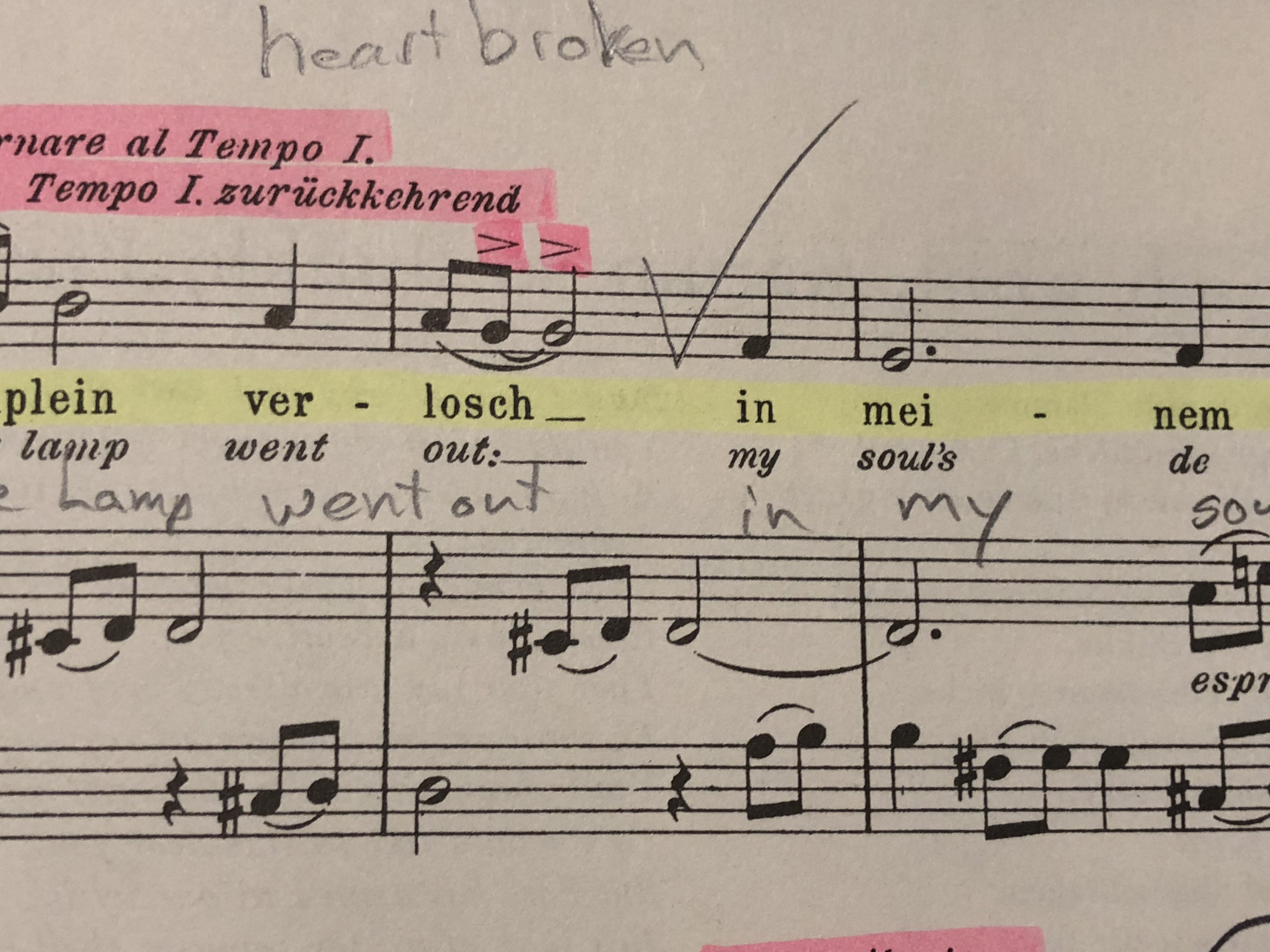

If the score has an English translation underneath the text, don’t pay much attention to it. It’s usually never accurate.

You need to literally translate each word into your respective language. This literal translation also needs to happen with your stage partners’ text because you have to understand what they’re telling you in order for you to form a reaction. Know the general idea of what they’re saying and underline their most important words, so you can react appropriately.

I write the literal translation directly into the score, underneath the original text, and I leave the score blank above the musical notes for anything I want to add about the music itself. This may seem obvious but it needs to be clearly written so you can understand what you wrote.

I make a choice NOT to translate any scenes I’m not in because think about it: my character wouldn’t know what’s going on in those scenes if he’s not in them. It’s good to generally know what happens but sometimes it’s good to not to know what happens because your character doesn’t know what happens. Like Marcello in La bohème. I can’t act like Mimì is sick until Rodolfo tells me that in Act 3. My reaction needs to be natural and taken aback, even though I already know that she’s been coughing up cats. The only parts that need to be translated are ones that describe your character, like if another character sings, “his mother died last year and has been grieving since”—it’s pertinent information to your character to act mournful.

I use Nico Castel for my translations because it’s reliable. It has the literal translations, the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) for diction, general translations, and directorial suggestions.

It helps to translate your own score with a dictionary when you’re first starting to sing so you can understand what that process is like. I don’t do it anymore because I’ve already gone through the process many times. Plus, I simply don’t have the time. Translating text yourself is the longer road but it’s the more fruitful one. I also keep an open mind when reading the Castel and rely on my own language skills to get me through a translation, something I didn’t have at a young age. So, whether you translate your own score or use a reference tool, the meaning is roughly the same. If you have any questions about something specific, have a conversation with your director.

Extra Credit: Another step for me in the translation process is creating my own booklet of the text. I usually copy the pages of my hand-written translations or the Castel and bind them together. I refer to that in my rehearsals more than the score, not only because there are way fewer pages but because I focus on my acting and telling the story more than my singing (which, funnily enough, helps my singing!)

4. Bang That Steinway

Now you can finally learn the music. This is an important skill to develop as soon as possible because it takes the most time. Coaches can help but they’re not always readily available and paying them by the hour is expensive.

I don’t think I need to give y’all a break down of how to learn music but take the time to solidify the notes and rhythms on your own. Repeat over and over again the odd phrases, large jumps, tricky text, etc.

I don’t separate the text out from the music and recite it as a practice method unless a passage is tricky to pronounce.

What I will do when I’m learning the music is underline the words I want to emphasize, which helps with the musical phrasing, since they go hand in hand. The emphasis might change places over time but you have to start somewhere.

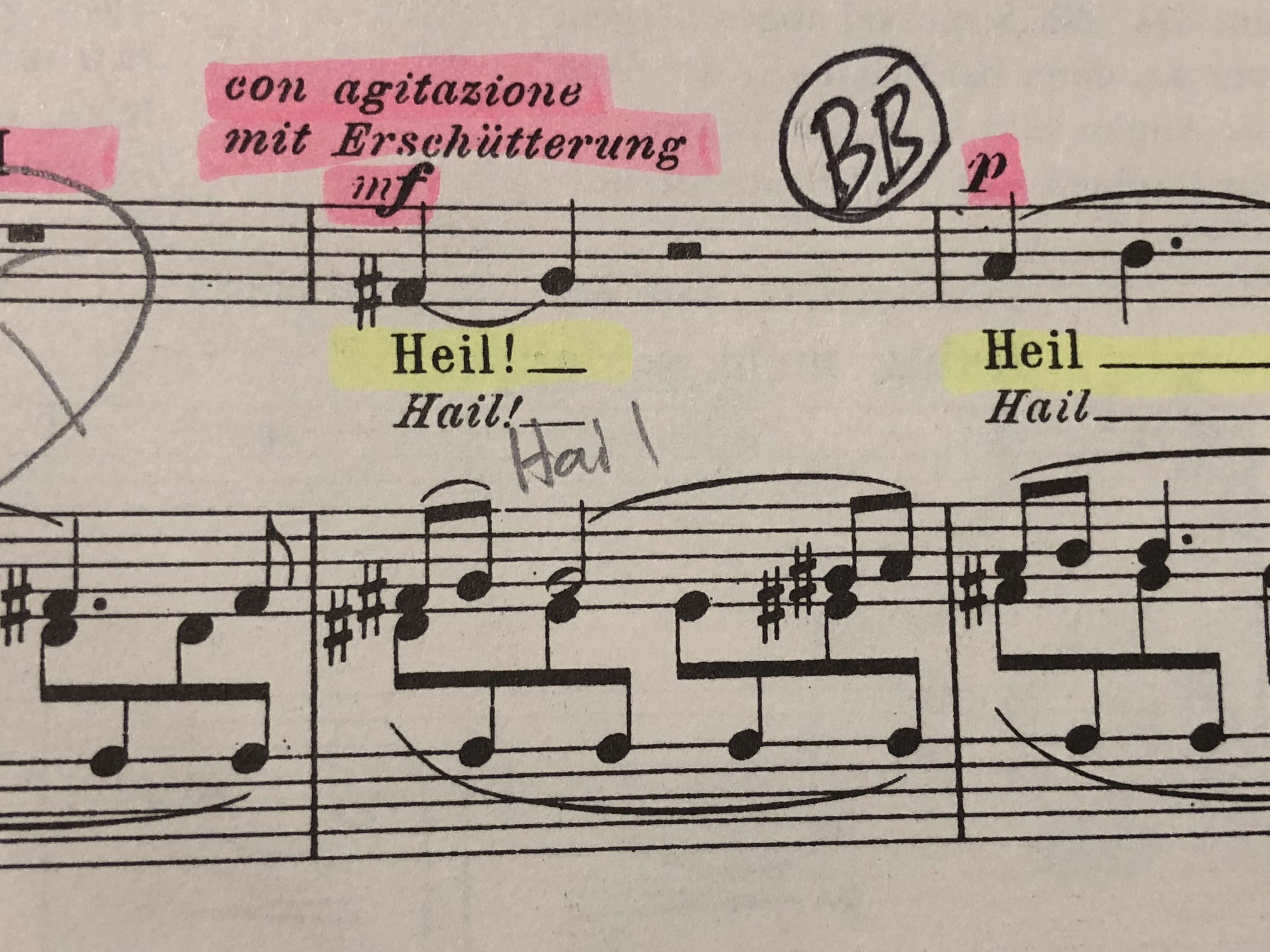

This is also when I write in double consonants and raddoppiamento sintattico in my score, as well as my breaths.

For a breath, I write a huge check mark:

and for a phrase that needs a really big breath before it (BB):

When learning a role, I practice about an hour and a half a day. Even if I’m not I’m in a focused practice session, I’m constantly running the music or text in my head.

5. Coach It

If you’re solid with the language, you probably won’t need a separate language coach but most singers rely heavily on coachings before that first day of rehearsal. A coach will play the orchestra reduction along with you so you can feel out the role as a whole.

When I was younger and couldn’t afford a coach (or wasn’t yet married to one!) for more than a few sessions, I would actually record him/her playing the orchestral reduction of my most difficult passages. I would later refer to that recording and sing along with it so I could nail it down. Even if I were a proficient pianist, their skills as a coach are invaluable for a singer and allows me to practice singing the role just as I would perform it.

The first coaching is important because you want to cover as much of the entire role as possible, to plan it out. Then you can go back and repeat the most difficult passages. After visiting with a coach, hit your voice teacher up to help you with any vocal challenges.

6. Memorize

Repetition, repetition, repetition!

Personally, melodies stick quicker in my mind than words do. I first memorize the music and the rhythms, singing it to myself softly over and over again. I memorize 2-4 measures at a time, then add it to the next 2-4 measures until I cover an entire system. I do the same with each system then add them all together until I have a page down. I do that until the entire role is memorized.

Usually, the text latches onto this process and gets memorized without me trying. Sometimes there are a few holes, so I diligently look back and make sure my text lines up just right.

After you’ve memorized it, look back at your score to check every pick-up note, breath mark, liaison, etc, is correct. You may have changed your musical ideas and phrasing choices from that first day you highlighted your score, so add those updates in. Also, you may slip up and forget some of the small details in the score, so make sure to check yourself.

That First Day

Upon entering the rehearsal room on that very first day, you should know every music note, rhythm, line of text, and translation as if it’s a part of you. Why? To prepare yourself for the chance that some changes may need to happen, like tempi, and rhythms, as you bring your artistic ideas to the table for the first time. A balance must be struck between you, the conductor, and the director, as they already have their own ideas as well. I find that my character interpretation happens naturally within rehearsals with the director.

I have a self-made schedule of knowing the entire score 2 weeks before the first day so I’m not cramming the days leading up. Cramming is vastly different than learning a role but it happens. On those rare occasions, this may help.

Background research helps, too. The first time I sang Eugene Onegin, I read Pushkin’s novel and I remember that his butler at one point brought him his comb set. This tells me that Eugene is incredibly conscious of the way he looks, and I needed to add that to my interpretation of him.

Role preparation should not be an overwhelming thing if you give yourself ample time to learn the music, stay organized, and remain open to the natural changes that might happen over time with your character. Most importantly, figure out what works for you. Nobody taught me how to learn a role, this is just my own process I’ve found from doing it 49 times. I wish you luck as you customize your own!

What do you think? Did you find this article interesting, entertaining, or helpful? Feel free to chime in with a comment below.

Do you get paid well enough for all those hours of prep?

I find that memorizing the LAST two measures firsr, then adding two measures back each time works well. The farther I go in a piece, the more familiar it becomes!

Reblogged this on howamazinglifecanbe's Blog.

Love it buddy! You do an excellent job of articulating the thought process behind your choices. The harder with that goes into it in advance equals a greater payoff in the end. One question for you. A challenge for many singers is once you learn something, and prepare it to the point where it becomes muscle memory, only to find out that you learned it incorrectly, or the conductor prefers a different way of phrasing, how do you re-train that muscle memory? I struggle with that. Nice blog man. Keep it up!

Work, not with. Could have proofread…