I gear most of my blog posts towards aspiring opera singers or young professionals but sometimes I like to mix it up and reach people who might not be in the opera world but are curious about it. So today’s post is all about why opera is known as the most difficult genres of music to sing.

Whether you’re dabbling or dripping with opera, I hope this post gives you some insight into opera singing!

This Thing Called Resonance

Compared to other genres of music, opera singers use more resonance when they sing in order to fill an entire hall with their sound. They don’t use microphones so their bodies become their amplifiers through an acquired vocal technique.

To achieve optimal resonance, each singer finds their own balance between their three in-body resonators: nasal, pharyngeal, and oral cavities.

A highly nasal voice, like The Nanny’s Fran Drescher or Gilbert Gottfried, has a lot of nasal resonance but the sound itself isn’t necessarily pretty and is fabricated. Practice at home by saying the word “ding’ and hold onto the final “ng”. That’s your nasal cavity, my friends. A darkened pharyngeal voice, like Darth Vader, doesn’t have enough volume or point to the tone. Try this one by imitating a ghost on an “oh” vowel. Finally oral or mouth placement is where most people naturally speak.

Over time and lots of training, I’ve found my mid-voice recipe for resonance is around—35% nasal, 50% oral, 15% pharyngal. After it’s found, you memorize that sensation, remind yourself of it, make minute adjustments, and recreate it time after time. It’s kind of like a recording studio soundboard in your body and you must adjust the levels of each resonator in order to achieve the desired effect.

Yes, some halls have more feedback, or echo, in them than others. Yet regardless of the hall, you have to be able to understand your voice and reproduce “your sound” under any circumstance.

The reason why resonance is a key factor for opera singers is that it allows their true voice to be heard with the utmost clarity, all without yelling. This can achieve varying effects, according to where a singer “places” their voice within their resonating chambers. The biggest goal is to achieve the loudest volume with a certain “ring” to the sound (in Italian, squillo). This is normally the sweet spot where we can hear the true beauty of the unamplified voice.

All three are options for vocal resonance placement, and finding a happy formula between them is opera singing in a nutshell.

Back To Nature

Everyone knows how to run. We never learn how to do it, you just start running one day. Now, if you overthink how your pinky toe connects to the ball of your foot and how your Achilles heel bends your ankle, you might fail at even taking one step.

Singing is similar. We hear music from an early age and join in with our family and friends with songs. It’s all around us when we grow up and it’s somewhat natural to us.

The first step to singing is breathing. What could be more natural than that? Luciano Pavarotti even said when asked how he did it, “I breathe, I sing.”

To put it simply, vocal sound production is a measured amount of air going over your vocal cords, over your tongue and out of your mouth. When you try to master something so elementary as breathing and vocal production at a very high level, it can get unnecessarily complicated. It’s a tough task of getting back to the basics of something innate. Undoing years of habits and bad form can lead to overthinking and overcomplicating.

The Total Performance

Opera has been around for centuries and that presents an interesting challenge for today’s audiences. It can be difficult to make certain operas accessible, because they may seem dated or archaic. As an opera singer, one must convince the audience to believe their emotions through their character. That story-telling aspect is unique to opera and musical theatre, and it takes a well-rounded performer to deliver such a show.

Even more so in opera, the characters at times sing about only one emotion and repeat words for five whole minutes, when it could have been conveyed in 10 seconds. For a fast-paced modern audience, that can get really boring. Especially when compared to other forms of entertainment like a movie, musical, or play. We constantly want things faster and it’s opera’s job to make those five whole minutes of repeated text mean something profound.

I believe that this “problem” with opera is also one of its strongest assets. When else in life do we get to simply kick back, open ourselves up to someone’s live art and spend our time enjoying something beautiful that elevates us to something higher than ourselves?

Languages

Another challenge of singing opera is that the singers have to sing in languages other than their own. Most operas are sung in Italian, French, German, English, and Russian. Unless you grew up speaking all five, you’re gonna have to put lots of effort into learning these.

Even if you’re a native speaker, the level of diction in opera is more elevated than everyday speaking because the words need to be heard over an entire orchestra.

Now, opera singers don’t need to be fluent in the languages they sing in. They learn the respective diction rules for each of these languages, along with the intricacies and “flavors” of each language by working with language coaches or listening to native speakers. This takes years to perfect since they have to sound as close to a native Italian or German speaker as possible since, as we’ve learned, singing opera isn’t already hard enough.

Opera singers translate each word and phrase into their native language, so when it comes time to perform, they know exactly what they are saying and allow the emotion of the words to steer their performance. That takes a lot of preparation because when the lights hit you, you gotta let yourself go with the character’s emotion, and without thinking about every individual word’s definition.

Until the Fit Lady Sings

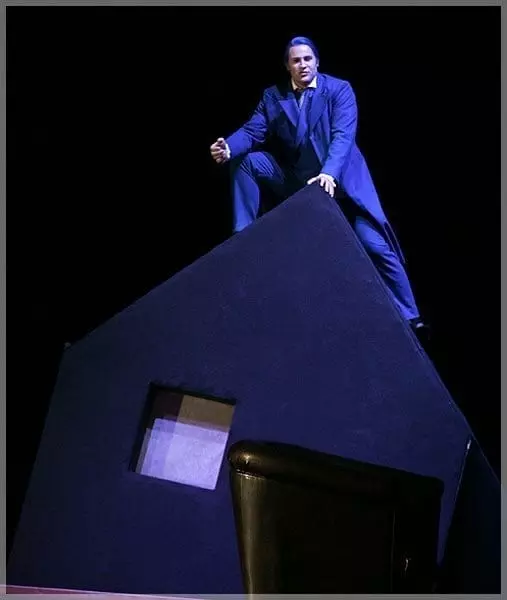

The physicality of singing opera is also challenging. Gone are the days of singers pulling up to the stage to “park and bark.” Opera singers nowadays use their bodies to portray their character in more and more interesting ways. I’ve had to sing upside down, on the floor, sliding down a fireman’s pole, hanging from a ship’s mast, on top of a moving house, etc. All of this is to be accomplished while singing with perfect resonance, air support, diction, and emotion.

The Tradition of Opera

We’re not done yet, folks! Also on the list of singing opera is understanding what goes into the style of this music. Lots of genres exist within opera such as bel canto, verismo, Mozart, Wagner, etc. and each of these have their own set of rules. You can’t go in with what you know about one genre and apply it to all others. This takes years of study and practice.

My point is that classical music exposure is limited in our culture and it’s not part of our everyday life. Unlike pop, country, and R&B, which are everywhere, we have to go out of our way to find it. You have to come across the opportunity to be exposed to it and then seek it out.

Vocal Limits

In opera, you’re physically limited to the number of performances you can do in one week. The human voice needs sufficient time to recover after singing over an orchestra for a 3-hour show. It’s just like how a marathon runner can’t run a race every day because their muscles need to recover. I shouldn’t sing more than three operas a week with at least a day in between to recover—not that I haven’t had to sing back-to-back shows—but a day in between is ideal. Musical theatre performers are impressive because they can sing eight performances a week. They use microphones to achieve this feat.

As opposed to a violinist or pianist, you can’t start fully singing until after you’ve gone through puberty. It takes a while for our voices to mature. The voice is limited due to its slow development. Have you ever noticed that there are no prodigies in opera? I’m not talking about America’s Got Talent “opera” singers. REAL opera singers. There are no 14 year-olds singing on the main stage of any opera house in the world. Your voice doesn’t fully mature enough to sing proper, large-scale opera until your mid-20s.

So there’s a lot of patience involved with finding one’s voice type. Even after years of allowing your voice to develop with age, there may be more years of studying on top of that to hone your talent. And 10 years after that, it may change again. That being said, your voice will constantly change throughout different stages of your life and you must regroup, reassess, and sometimes reinvent.

#OperaSingerLife

By far the hardest thing about opera is the uncertainty of a career. After mastering all of the previous things I’ve mentioned, it doesn’t guarantee you shit. I spent 8 years at 3 different universities and 2 years in an internship. That’s 10 years of study with no professional safety net. There is no guaranteed pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Because there are no gold medals in this field, you can only move towards goals that are then replaced with other goals. You need to exhibit a lack of complacency. Yes, there are different statuses within a career and after a point, more jobs start to pump out for you, but there is no destination. Even with the success I have found for myself, I have to scrap every day to keep my place in the sun.

Strangely enough, the most difficult thing about singing opera—that never-ending road towards transcendence through art and something bigger and better than ourselves—is also the most rewarding. No matter how close one gets to the top, there’s always room for growth. Some nights I feel like I’ve reached my next level and some nights I don’t: even if I have given the best performance of my life, I know I can still do better. And even if I do have a so-so night, I don’t let it get me down. Instead, I think of the bigger picture and find those moments to bask in the collective greatness that is this art form.

What do you think? Did you find this article interesting, entertaining, or helpful? Feel free to chime in with a comment below.

Thank you!

Amazing article!

I am a retired professional violist, (Radio Filharmonisch Orkest Holland). I formulated it thus: One day, I reach for something new and achieve it. I feel as if I am the best in the world! Then the next day, what I achieved yesterday is the new “ordinary” and I reach higher but I fail and feel as if I am the worst in the world. The truth is somewhere in between! Not to mention having to find a new way of making music: In an orchestra, you have to blend in. The conductor decides WHAT you play; HOW LOUD you play it; HOW FAST you play; WHAT TIME you play; HOW LONG you play; WHEN the coffee breaks are: WHAT YOU WEAR; WHERE you play. Suddenly, there you are, with no one to blend in with, and no one making those decisions for you! Talk about an identity crisis!!!

Hi Marilyn, that’s exactly the plight: there is no destination, just the daily self-improvement. So we must enjoy the process.

I found this incredibly helpful as a mother of a rising artist in opera. I never knew what goes into singing, the work and discipline for this art. Thank you for this new perspective. I look forward to begin to enjoy opera now that I understand more. 😊

So glad you enjoyed the post Cheri. Best of luck to your artistic child!

I gave up opera as I felt it no longer represented me as an artist. I’ve written a lengthy post on it on my blog.

THE hardest thing to do… classically sing with no microphone… the years of study, language and musicianship… but also the most glorious when done well. I call classical vocal music…the language of emotions and the voice of the soul.

Beautiful

Loved the article! My mom was on Broadway preforming in musicals, I never understand why she continued to train in opera even though she was singing opera on broadway. However, now having been trained in opera by her, I have grown to appreciate it so much, specifically because the emphasis on breath control has allowed me to be able to sing almost anything in any style! I am not a gospel singer but I and very grateful for my opera training.

You’ve got a great perspective!

Yes! The technique that I learned from studying classical music has served me extremely well, although I only sing Jazz Music, while accompanying myself on the Piano! Also, the languages that I studied with Classical Music gives me a great advantage to use them in Jazz Music, too! Great Article!

Great! So, you are not the gospel singer Le’Andria Johnson? Yes, there is a world famous African American gospel singer with that name! Just asking! She is so phenomenal with the greatest gospel voice I have ever heard. Le’Andria, Mahalia Jackson, Shirley Ceasar and Aretha Franklin are the best gospel singers ever to walk the earth, I think! I enjoyed the valuable information discussed in the article, as I am a professional Jazz Singer/Pianist who comes from a totally Classical Vocal and Piano musical background. So, I agree from experience with everything the writer has stated in the the article!

Great perspective on the opera world and what it takes. I have newfound appreciation for the craft after becoming a Dear fan of a singer named Dimash Kudaibergen, from Kazakhstan. He is classically trained but decided on a different, more global path. There are many elements of his opera training in many of his magnificent performances. Please check him out, you might be pleasantly surprised at how he is bringing the masses to the opera sound.

A wonderful article I love it very much so helpful and INTERESTING.

You’re all wet. The nasal, pharyngeal and oral cavities are secondary. You don’t try to place it in any of those. I am an a amateur soprano opera singer and I learned trial and error by my self. I have been singing for almost 40 years. I am 71 and still have high C. Currently, I sing Ave Marie (Gound-Bach), Valse from Romeo and Juliette (Gounod), Casta Diva (Bellini), Visi D’arte(Puccini).

The little known secret is one needs to lift the voice through years of practice.Don’t sing on the tone, that sounds flat. Sing a little above, but not sharp either. The sound will have a natural zing All babies are born with a natural overtone and we lose it as we grow. That’s why their crying is so penetrating. LIFT-UP LIFT-UP LIFT-UP LIFT-UP. It’s that simple and takes years.

You’re all wet. The nasal, pharyngeal and oral cavities are secondary. You don’t try to place it in any of those. I am an a amateur soprano opera singer and I learned trial and error by my self. I have been singing for almost 40 years. I am 71 and still have high C. Currently, I sing Ave Marie (Gound-Bach), Valse from Romeo and Juliette (Gounod), Casta Diva (Bellini), Visi D’arte(Puccini).

The little known secret is one needs to lift the voice through years of practice.Don’t sing on the tone, that sounds flat. Sing a little above, but not sharp either. The sound will have a natural zing All babies are born with a natural overtone and we lose it as we grow. That’s why their crying is so penetrating. LIFT-UP LIFT-UP LIFT-UP LIFT-UP. It’s that simple and takes years.

Very interesting but surely “That story-telling aspect” is not “unique to opera and musical theatre” but equally important in lieder singing or any performance by a singer accompanied by a single instrument. Here a singer must work really hard to convey to the audience the character and emotions in the songs.

That is a mighty challenge

Yes! The technique that I learned from studying classical music has served me extremely well, although I only sing Jazz Music, while accompanying myself on the Piano! Also, the languages that I studied with Classical Music gives me a great advantage to use them in Jazz Music, too! Great Article!

Thank you! Great article