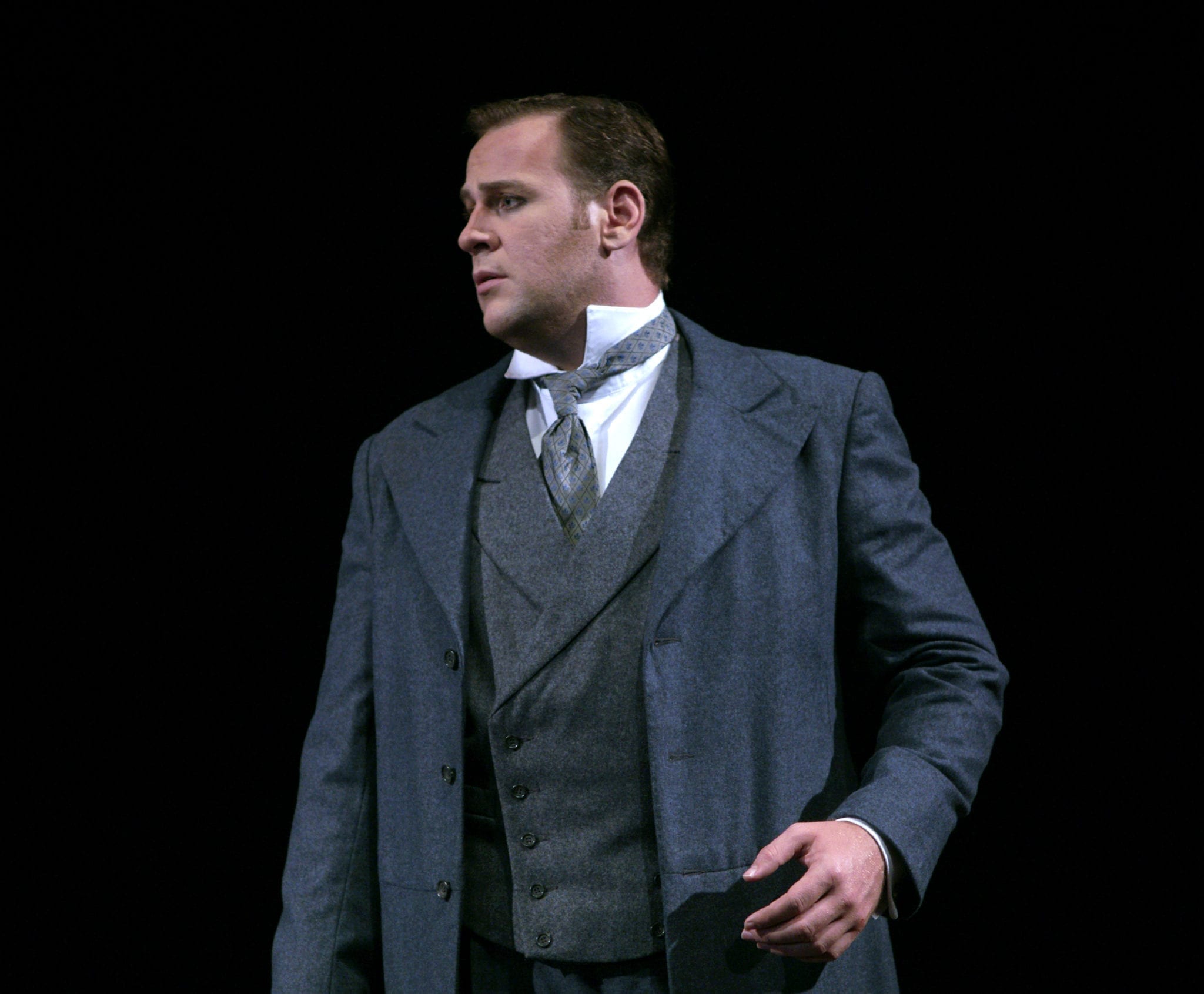

When a baritone steps into Verdi territory, it’s a pretty big deal. A lot of new, exciting, and prolific roles open up and a whole new world emerges. There’s a lot to singing Verdi and with my first role as Germont, I’ve learned a great deal. Not only about this new fach but about this legendary opera and the imperative role Germont plays.

Germont From Within

La Traviata (which roughly translates to the fallen woman) takes place in late-19th century France. This timeframe is important for the story because the main character, Violetta, is ahead of her time. She embodies feminism in the strongest sense of the word by living an independent life and doing as she pleases, on the outskirts of high society. Her counterpart, Giorgio Germont, is the opposite. He represents the constricting social norms of the time. He is old-fashioned and very much “of society.”

These two opposing forces create the catalyst for this opera. The drama of Violetta’s impending death is central, but the conflict begins to stir once Germont enters her life: he tells Violetta to leave her lover, his son Alfredo.

Germont convinces Violetta that it’s the proper thing to do. Because of the morals of the time, his judgement is clouded. Violetta and Alfredo’s relationship risks the family’s reputation and his daughter’s engagement is at stake. In the eyes of Giorgio Germont, this isn’t a heartless thing to ask: social pressures deem that it simply must be done.

Back then, there were many deaths attributed to tuberculosis, but it’s tragic to the audience because it’s thrown into their faces. It was an everyday tragedy for that time, but the audience grows to care so much about Violetta because she is so inspiring. They see themselves in her…this free, libertine person fulfilling their desires and passions without caring what others think. And then comes Germont tearing it all down.

Fatherly to a Fault

Germont’s motivation is his family and their honor. His intentions to protect his daughter are noble, but at what cost?

In the end, Germont gets his way but not without victims involved. He learns that his righteous and one-sided ways may not have been worth it. Instead of convincing Violetta to leave Alfredo, he could have allowed them to be happy together during her final days. He could have told his daughter’s fiancé to screw off. We all wish that! Yet without Germont’s role in this opera, the enormity of the tragedy ceases to exist.

At the end of the opera, Germont admits to feeling regret for his actions. He realizes only too late that Violetta is sound of heart and possesses a beautiful spirit. Perhaps his religious morality and desire to maintain a certain image in society wasn’t worth the price Violetta was forced to pay.

I find it interesting that the story we aren’t told is the supposed happy marriage between his daughter and her fiancé. Maybe for La Traviata: The Sequel?

Dramatic Challenges

All of that being said, the biggest challenge in performing this character is finding the balance between liking Violetta and sticking to his own code of honor. As a performer, Germont can’t like Violetta too soon. He has to like her too late. That balance is hard to find.

The music is so beautiful (and you can get too carried away with that) but keep in mind, he’s a manipulative guy with the sole purpose of preserving his family’s honor. For him, it’s a slow-boil of coming to terms with the fact that he actually cares about Violetta. Even though Germont defends Violetta when Alfredo disrespects her in public, likewise Germont disrespects Violetta, but in private.

Sadly, Violetta’s death solves all of Germont’s problems. Alfredo can’t be with her anymore, and so his daughter will be happy. Alfredo might even go on to marry a proper woman in high society. He’ll be destroyed and heartbroken, but he’ll get over it. Germont’s actions create other problems he can discuss at length with his wife or psychiatrist, but he didn’t lose the love of his life or die of tuberculosis.

Portraying this character takes a huge amount of gravitas. He is controlled and mature. Germont is a man who is in control. This is only found through experience, and the practice of relaxing on stage without getting nervous: you can’t fake it. It’s takes a mature actor who realizes that less is more.

My favorite part is when I can let that “tough guy” mask fall away. The mask of being proper and always in control. I let it crumble to pieces when I realize I’ve taken away this poor woman’s final chance at love, and that’s the real tragedy.

The Waiting Game

I first sang this role 2 years ago but I wasn’t ready. Vocally speaking I was, but not stylistically. I didn’t know that I didn’t know the bel canto style, you get me? I realized I had a lot to learn before I sang it again and I went to Italy and studied bel canto style.

I don’t want to put restrictions on anyone, but with the natural development of the baritone voice, I would suggest that if you are under 25, don’t look at this role. It takes a deep understanding of style and a maturity to the voice that only comes with age. Other than vocal preparedness, there is an evolution to a singing career, and if you’re already singing Germont at 25, what are you going to sing at 40?

Germont is my first Verdi role simply because it’s done so often. Posa in Don Carlo would have been a slightly more natural first choice but beggars can’t be choosers.

The aria, “Di Provenza” is the most difficult part of the role for me. It takes immaculate Italian, mastery of singing in and through the passaggio, legato lines and vibrato on every note. Lots of classy singing. Classy as in a three-piece suit, gloves, cane and hat, classy. You can’t ever punch, shout, or hook a note. You need to relax into the passaggio phrases while spinning without overdoing it. This is when I stop in the opera and just focus on my singing.

If you’re going to offer “Di Provenza” in an audition, make sure it is within your brand. If you are a Verdi baritone, offer “Di Provenza” and late Donizetti/Bellini, Ford’s Aria, etc. But if you are a lyric baritone, stick to an aria that fits with that kind of package instead.

My favorite line in the opera is when I sing, “Pura, siccome un angelo.” The way he sings about his daughter touches my heart: saying that she is as pure as an angel. He opens up and shows his true heart. Germont reveals that he, in fact, doesn’t disapprove of Violetta but he is asking her to leave for the benefit of his family. He’s so sincere, even though it’s the wrong thing to do.

Addio del passato

I feel like I am stepping into my future with this role, without having to close the book on Rossini and Mozart. Singing Germont, I’ve learned it takes a special kind of effort to sing bel canto: it almost feels like I float on a pocket of air since the air control is more consistent throughout a phrase. The level of concentration it requires to keep the sound spinning is substantial and I feel rooted to the stage, singing with the deepest, most sustained breath. This kind of singing is very secure and feels good physically on my system of support. It makes me feel invincible.

I am thrilled that a second road of repertoire with this new kind of bel canto singing has opened up to me, and I look forward to exploring it even further.

What do you think? Did you find this article interesting, entertaining, or helpful? Feel free to chime in with a comment below.

0 thoughts on “How I Role: My First Verdi | Germont”